NCUIH Native Healthcast

This is the official podcast of the National Council of Urban Indian Health (NCUIH). These episodes elevate conversations about Native health and the development of quality, accessible, and culturally competent health services for American Indians and Alaska Natives living in urban settings.

Produced by: Jessica Gilbertson, MPA (Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa), Director of Communications and Events at the National Council of Urban Indian Health

NCUIH Native Healthcast

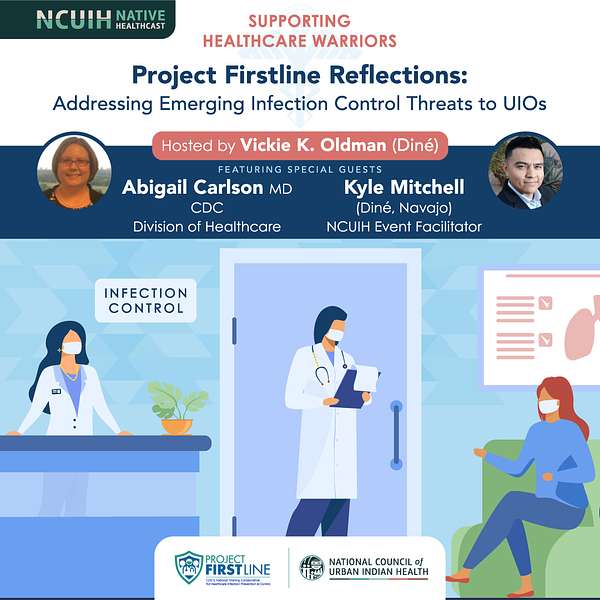

Project Firstline Reflections - Addressing Emerging Infection Control Threats to UIOs

Welcome to Episode 2 of the NCUIH Native Healthcast!

This is the National Council of Urban Indian Health's (NCUIH) podcast platform which is promoting infection prevention and control education topics for our frontline warriors and healthcare team members through collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention via Project FIRSTLINE.

Our guests for this episode include Kyle Mitchell and Dr. Abigail Carlson. Kyle is Diné (Navajo) and is Storyteller and facilitator working with the technical assistance division at NCUIH in Washington, DC. Kyle is a decorated army veteran and a purple heart recipient, as well as the bronze star with valor. Dr. Carlson is one of the infection control advisors and subject matter experts for Project FIRSTLINE and works within the CDC's division of healthcare quality promotion. She advises the team on the development of the project first-line curriculum, supporting resources and training modalities, serves as a primary subject matter expert for Project FIRSTLINES training opportunities, and helps provide strategic directions for the future of the collaborative.

Our host is Vickie Oldman, Diné.

* Project FIRSTLINE is a national training and educational collaborative led by the U S Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to provide infection control training and education to frontline healthcare workers and public health personnel. The contents of this podcast do not necessarily represent the opinions or policies of CDC or the United States Department of Health and Human Services (H.H.S). and should not be considered as an endorsement by the federal government.

Vickie: Welcome to the National Council of Urban Indians Health podcasts on infection prevention and control education topics for our frontline warriors and healthcare team members. Serving American Indians and Urban Indian Health Organizations. Yá’át’ééh, hello my name is Vickie Oldman. Your host for these broadcasts.

I am, Diné (Navajo), a resident of New Mexico and have been working with Native communities and nationally for over two decades as an independent consultant. In these. I will be interviewing leaders, advocates, and practitioners with a focus on infection prevention, control strategies, and Urban Indian Health care settings.

Ahéhee', thank you for joining us. Project first-line is a national collaborative led by the U S Centers for Disease Control and preventing (CDC) to provide infection, control, training, and education to frontline healthcare workers and public health personnel. The contents of this podcast do not necessarily represent the opinions or policies of CDC or H.H.S. and should not be considered an endorsement by the federal government.

I would like to introduce our first guest Kyle Mitchell, whose current role is a contracted trainer and facilitator with the technical assistance division at the National Council of Urban Indian Health in Washington, DC. Kyle is a decorated army veteran and is a purple heart recipient, as well as the bronze star with valor.

He is a graduate of Arizona State University with the focus and communication as a program manager with a background in business development, he found it Kiiłtsoi bitó’ which translate to (bushes where the yellow flowers) are an organization that provides a professional service in sharing. As a trainer and facilitator, Kyle serves as the senior program alumnis at South Mountain Community College.

He uses storytelling to connect with the Indigenous students. Kyle, thank you so much for being here.

Kyle: All right, thank you Vickie. Good morning everybody thankful to be at this podcast today.

Vickie: Wonderful, do you want to add anything more to your introduction, your clans, and also maybe correcting me with how I pronounced it, the organization.

Kyle: Oh yeah, no problem at all. No problem at all. So hello there everybody, my name is Kyle Mitchell and I am Diné. So within the Diné culture, we always introduce ourselves. We do this because that's how we link a kinship. So in Navajo culture, we believe that everybody in the world has four clans, because everybody has a mother, a father. Your mother has a father and your father has a father. And so that's how our clan systems work. So with that. Yá’át’ééh shiyé Kyle Mitchell yinishyé (Hello, I’m called Kyle Mitchell), Tó dích'íinii dóone’é nishłį (I am of the Bitter Water clan), Naakaii báshishchíín (I am born of the Mexican People clan), Kinyaa’áanii dashicheii (Towering House are my maternal grandfather), Naakaii dashináli (Mexican People clan are my paternal grandfather).

So hello everybody, I am Tó dích'íinii, so that's Bitterwater, that's my main clan and earlier Vickie, when you named the word it's pronounced Kiiłtsoi bitó’ (bushes where the yellow flowers) and so that area is, just outside of Dilkon on your way towards Bird Springs. And there's a mountain that looks like an anthill people say, but that's what we call

Dził Nóódóózii the mountain with the streaks on it.

And so that's where I was raised from. And so as you know, with any Indigenous community, we're very descriptive. And so that word it's we be tour. will tell people within that area exactly where I'm from, and what family I come from. And so with that, I decided to start Kiiłtsoi bitó’ just to help out a lot of youth within the urban environments, actually.

And I'll talk a little bit more about that a little bit later, but that's my intro.

Vickie: Thank you for that extended introduction. I appreciate you sharing your clans and also letting folks know what that all means. And also letting us know where your roots are from. Again, welcome. This is exciting. Can you tell us a little bit about how you became a part of this team at NCUIH?

Kyle: Oh yes, definitely. Well, first and foremost, I have to give shout out and praise to Evie Maho, she is the one who really wrote to be into this project, which is phenomenal. The things they're doing at NCUIH are just unbelievable. So I meet Evie years ago, which she was working in Phoenix with need of Native health there and they were looking at extending their urban garden at that time.

And so she reached out to me to see if I could do a storytelling on them, harvesting a little bit more on the planting and just, you know, give people some indigenous knowledge surrounding that. And so I did that through the modality of storytelling, talking a lot about how within Navajo culture that we emerged and what seeds we brought with us in a place they have, it was phenomenal.

And so through that, Evie and I were able to work together. And, outside of that, Evie moved along obviously and landed here with NCUIH and the emphasis with working with urban Natives. And so she reached out to me and told me about the position, well, the potential opportunity. And then she followed up quickly with the apply now at the end of that email.

And so I applied and I've been on with them for just a bit now, but I'm excited and looking forward to it. So for those of you who are not familiar with, with Evie, she is the program manager and the department of technical assistance in research center at the National Council of Urban Indian Health. And so that's how I came to be here today.

Vickie: Beautiful. Thank you. Yes. A shout out to Evie Maho and all that she brings to NCUIH. And again, that just shows the power of networking and connection and relationship building. So thank you for telling us how you arrived at NCUIH and also appreciate you talking a little bit about storytelling, is that it's a nice transition to this next question that I want to ask.

But before I ask the question, I want to read this quote that you offered. And I found it very beautiful. And I would love for you to just talk a little bit about it before answering the question, but what you had shared, and quote is "within Navajo culture, at least the way I see it, and the way I've been brought up is that we always move forward.

We move forward with three things, songs, prayers and stories. So everything we do in our culture is related to these three things." So beautiful. I just had to read that. And when I read, I read it several times and I was like, oh, this is, this is beautiful. And so with that in mind, you know, you talked a little bit about your storytelling.

Tell us, um, a little bit about this, but also how this translates to your role with the project first line team at NCUIH.

Kyle: All right. So, all right. Well, first and foremost, I love storytelling. Like absolutely love storytelling because at the end of the day, storytelling is the fiber of our human connection.

Right? When we look at Indigenous communities and we look back, we do not have written translation. We don't have a lot of dialects or anything. Well, visuals, we don't have a lot of those things. So instead what we have is oral. So when that's really how storytelling you know started. And so within the context of Diné culture, um, which is predominantly equal to a lot of Indigenous communities, is the stories were passed down from generation to generation.

But with storytelling, what we do, is we take the information that was from the past and those stories that were given to us. And then what we do is we craft that story to meet the audience in front of us at the current. Right. So for example, I always tell my students when I'm teaching is, you know me to tell you the same story of Mary had a little lamb, but I'm gonna tell it in today's context and not tell it you know in the 1800's to where it would take on different verbiage, take on a totally different light.

And so really that's what storytelling does more intimately to me, storytelling is everything. You know, I grew up, up on the Navajo reservation with my grandparents. We didn't have, we still don't have running water actually. We just got electricity about 10 years ago. And it, every day my grandparents would tell me stories.

They would tell me about the sun rising why it rises when we're working outside. They would tell me why it's important to work, why it's important to set these goals in life, to do these things. And so I, I grew up taking all of that for granted, actually, you know, just thinking that , every Navajo kid was growing up the same way I was.

And I, didn't see how it pertained outside of my culture until I was taking classes at South County Community College. And that's when I really got into storytelling. And what I noticed is when I started doing storytelling, there was all of these Native youth within the Phoenix metropolitan area that were always there.

They're always asking follow-up questions when to shake my hand, you know, just little things like that. And the more I started noticing the power of storytelling for them. because a lot of this, a lot of the youth there were maybe second generation urban Natives, I guess you would say. And so a lot of them had really no correlation or no connection to the traditional teachings.

And so with storytelling really, that's what I did and I'm so grateful. Cause I've worked in higher ed for about six years now. And ever since I started, I started working specifically with Native youth within the metropolitan. And so as I'm sharing stories that leads into questions about identity, that leads into questions about culture.

And so I was able to cultivate that and I tell the students all the time. You can buy a book, you could keep that in your shelf and that's great. And all, but the three things that are really going to take you far in this life as an individual and especially being Indigenous are going to be those songs, stories, and prayers, because that's what cultivated and built up our ancestors to push ahead.

And even as we're talking about COVID-19 and we're talking about strains and things like that, those are the things that as Indigenous people rely on, you know, we really look to what type of teachings, when have we seen this before in our past and how have we combat it at the time? And what can we do now? And so I'm just really grateful to be part of a NCUIH in that way of where, you know, we can blend somewhat of the traditional aspect and the Indigenous knowledge wheel base with what the CDC is pushing out to our relatives in the cities.

And so how that all relates and why I'm here today is because storytelling really , brings that human experience, right? So it's able to take all the data, all of the roll-down that's coming from the CDC, and I'm able to make it more palatable for the audience, because we're really looking at helping those FirstLine workers, those individuals who are on the front lines, and we're just giving them all that information.

And so when we do that through a story base, it's a lot, like I said, a lot more palatable and it's smooth and easy going. And the greatest thing is at the end of every story, there's a point behind it because if you just talk, you're talking right? But the story always has a point at the end. And so what I'm really trying to nail through with every presentation is the point of what we're really doing within the organization.

And so within training, within the virtual settings, that's also very easy because as you know, storytelling is, um, it can be oral, but it's also great when you can see the visuals, right? You see the person, you see their smile, their sad face, so on and so forth. And, uh, just looking to bring all the tools within the wheelhouse.

I have my prior knowledge and just give it my best to share out this information to our relatives

Vickie: Nizhóní (beautiful). Thank you. I love, love, love how you had noted. Storytelling is a fiber of human connection. I was like, oh, I love that. I love that. And also how story telling attracts right? Like you're, you're listening in a different way, I feel like , when you're in a deep story, you're listening with your whole being your whole body, your whole, your heart, and it, and it sits with you, your body's processing it and it's also actually reacting to it in a different way. So I think that's also, what’s powerful when he had said how it tracks. It made me think beyond, beyond attracting people, but I think how it's affecting folks. So I think it's beautiful that you're going to be using this modality to really help draw in, what does this mean? For folks to sort of remember- sort of that muscle memory, how we should be, be healthy and how we need to be careful and be safe.

Right. I appreciate that point. Anything else that you want to elaborate before I go to our next question? Well, you know, the other thing and thinking about our audiences are going to be universal, right? So we're not going to be just talking particularly the one tribe. We're not going to be talking specifically just with region.

This is going to be nationwide. And storytelling is really truly that because of the points you set, right? It captivates people it draws them in, and some more of that people can soak in the information, the better it's going to be. And again, you know, storytelling is, what I have found to be the best modality for that.

Kyle: So, thank you.

Vickie: Yes. Thank you. So NCUIH had a webinar on January 28th and it was titled “Addressing Emerging Infection Control Threats to Urban Indian Organizations”. It was described as a gathering Kawe. Can you tell us what Kawe, Kawe means? And how this is relevant to the training events on infection control?

Kyle: Oh, yes, definitely. So Kawe is a Comanche word for “gathering”. And so when the NCUIH is looking at these rollouts in these different areas and being within the urban environment, usually within a lot of Indigenous communities that are more urban, right? So I'll use Navajo for example, we have chapter houses, right?

So when something's going down on the rez, you have need to find out, go to the chapter house. Well there's, really nothing like that in place for the urban population. And so, they termed the word Kawe to kind of replicate that meaning of a gathering of Indigenous peoples within one place. And so it's something that, you know, you don't have to be part of that particular tribe, you know, but everybody within the urban environment is always trying to gather and trying to pull together and cultivate that community.

So we're just taking it a step further and naming, and calling it what it is. So with that, you know, community is something that is universal for all Indigenous communities. You know, something that we all can relate to. Within Navajo again, we have our clan ship, right? So we have that one step further into kinship. With other tribes along the east coast, they have different origins, right?

They have different stories that they tell, but everything is surrounding gatherings. So for all Indigenous communities, and one thing, I think that the nation and the world got to see was how Navajo mobilized during COVID-19. Right? So normally we would meet in chapter houses. We would start talking, we start doing this, but what we did is we had to meet with the times of today.

So they were able to use the online modality to cultivate a gathering space, right? Virtually everybody was there, they were healing. They were hearing the real-time information that was coming out. And that's really what we want to do. We just want to replicate that same model of community within those urban environments for those natives there.

Vickie: Nice. So do you guys include music and food?

Kyle: Maybe for our in-person gatherings.

Vickie: Soon I hope, I don't know. Every year I keep thinking this is going to be the year, but here we are still in it. The webinar on the 28th had actually did a polling and the polling asked them a couple of questions. It asks whether infection control practices are improving in the workplace.

Majority of the participants answered yes. 22% indicated that they were not sure. So when asked, what would be most help at this time? Majority of them had said we need more training. So we gathered that the infection control practices are indeed improving, but healthcare workers, still feel that they need more training.

So how will NCUIH provide IPC training that can reach healthcare workers in various capacities?

Kyle: All right, thank you for that. So NCUIH is going to continue to provide webinars style trainings, quarterly, which will share the CDC project first-line development on content materials. So, the webinar we had, and we were just giving updates, the roll-down from CDC is coming to us, and then we're going to roll that out to everybody. So those are available online. We will also provide communities of learning, such as project echo, extension for community healthcare outcomes, where UIO's will get a chance to work on issues in infection control together.

And so those are other opportunities, we're opening the doors for individuals to participate in the work that we're doing. And the last thing is we're continuing to share training materials on our website, also through social media and on our newsletters, as well as other training platforms. So we're really trying to do everything we can.

So that way we can at least bring people into, what's happening right now and providing that up-to-date information. So if they have any questions, I would say to check out NCUIH, check out our website. There's a lot of resources there. You can find various things. If you're not too savvy with that, you can look on some of our social media platforms and find information there as well.

Vickie: Great. Thank you. So just thinking about your role with the NCUIH and the webinar, anything else that's percolating for you or that you want to emphasize or add to?

Kyle: I just really want to emphasize and applied NCUIH for taking this special approach to our urban Native population, because in all honesty, there's not a lot of resources for our Natives living in those urban environments.

There's maybe one or two small nonprofits that are getting just urgent care service. So when we're able to share information like this and it's coming from more of a Native connection, right? So they're able to [00:19:00] empathize a little bit more with us, than to make it more digestible for them as they're hearing the webinars and the information that's rolling down.

And so I would just say that, we are targeting and focusing on our urban Native population.

Vickie: Thank you so much. I appreciate you sharing. And we look forward to hearing more. So I want to transition a little bit to our guest speaker that appeared on the webinar and here's some of the learnings there.

Dr. Carlson was the guest speaker at the webinar hosted by NCUIH on the 28th, as I had mentioned, and she engaged in Kawe, "the gathering" to discuss current infection control threats to UIO's and other guests as well to the project first-line team at NCUIH. I want to introduce our guest speaker today on the podcast.

Dr. Abigail Carlson is one of the infection control advisor and subject matter expert for Project FIRSTLINE CDC's new training collaboration for Health Care Infection Control. She's with the CDC's division of healthcare quality promotion. In this role, Dr. Carlson advises on the development of the project first-line curriculum, supporting resources and training modalities, serving as a primary subject matter expert for Project FIRSTLINES training opportunities, and helps provide strategic directions for the future of the collaborative. Immediately prior to joining CDC. Dr. Carlson was an assistant professor of medicine at Washington University in St. Louis. Very impressive. Thank you so much, Dr. Carlson for being here. Welcome our listeners.

Dr. Carlson: Thank you. Thank you so much for having me, hello everyone. It's a pleasure to be with you all today.

Vickie: Do you want to elaborate and say anything more? I know sometimes it's hard to hear people read about our stats, right? But anything else that you want to share that a little bit more personal?

Dr. Carlson: Yeah, I know you got the long version of the biography, but yeah, I am

originally from Minnesota and have traveled around the country and around the world in my educational pathways, but spent the vast majority of my time in- actually Northern , Minnesota, the ancestral lens of the Ojibwe people and I came to CDC during the pandemic. So I have actually moved down to Georgia.

In my time before CDC and my time at the beginning of the pandemic, I was working as a clinician at the St. Louis VA, where I was seeing patients and also working as what is called a healthcare epidemiologist, or hospital epidemiologist, which is kind of like a mini CDC for the hospital is the department of hospital epidemiology and infection prevention.

Where really we're responsible for preventing infections inside healthcare in a variety of ways. That's a pretty fun role, extensive role, but came over to the CDC just because I had this opportunity to expand this infection control education effort beyond just an institution and out into the, the wider world.

So that's how I got here. And, in this role.

Vickie: Thank you. I appreciate you, first of all, adding more color to your biography because I think that's important. It's important for folks to get a sense of what your roots as well, where you're from. So I appreciate that. I also appreciate you acknowledging the lands that you're on, and what I also appreciated about your introduction is, talking about you being on the front lines. Like you understand, what our practitioners, our frontline warriors are experiencing. So you've kind of seen it at different angles, and I think that's really beautiful and helpful, particularly in the role that you play now. So thank you for all of that. I wanted to ask the first question about Project FIRSTLINE and your role specifically with this collaboration?

Can you tell us a little bit more about the services that are being provided?

Dr. Carlson: Yeah. So Project FIRSTLINE is quite, quite the project. Sometimes it feels like we're doing a little bit of everything in the world, which can be both good and overwhelming, but the core mission of what we do is to bring healthcare infection prevention and infection control training to frontline healthcare workers. So a lot of the training in the past has been an education in the past, has been focused in on the clinical professions, the nurses and the physicians in the healthcare setting and that is needed. But in the pandemic what's become very clear is we're missing everyone else.

And really, frontline healthcare workers have the experience and capacity to prevent infections in many many different ways, if they're given the knowledge they need to do that. So our goal is really to bring this down to the people who are doing the everyday work, whether that's, you know, the first person you see in the door at the information desk and checking in, or whether that's up to the physician.

The physician's assistant nurse practitioner that you see to get diagnosed and treated. And then there's all sorts of people in the middle that often go underrepresented in this, so your environmental services workers, your dietetics workers, so the people who are making your food, the people who are scheduling the appointments, the people who are making sure that the elevators are working and that the lights are functioning.

All of those people are healthcare workers and they just, they take on different roles in the institution. So that's who we're aiming for. It's a big crowd, but hopefully one that will find a usefulness out of what we're doing. The things that we're doing are very diverse. So some of the things are like this podcast and the webinars that NCIUH hosted we're trying to come out of sort of behind the wall that sometimes is the CDC and say, no, we are people. We do in fact, exist and talk and want to talk to you about your experiences and sort of share where we're coming from, as we bring out our recommendations.

As Kyle said, do it in a way, that resonates with you, that, that speaks to you in your place with your cultural background, with your context.

So that's part of what Project FIRSTLINE does with a variety of partners. The other thing that we do, or the other major thing we do is to create training materials. So we started in year one when we were just starting out and we're trying to get things done fast with videos, which is mostly me standing there talking about certain topics that we hope are of interest and use to people.

You know, what do we mean by respiratory droplets? What are they, how does COVID-19 spread through respiratory droplets? What do we mean when we say asymptomatic transmission? How best to do cleaning and disinfection? Those sorts of things, we started with those kinds of materials, we've built those videos and now in the second year, we are definitely moving into products that you can use right on your computer. Short little module, and we're talking minutes, five minutes, 10 minutes, definitely not your traditional 60-minute course, most of the time. Ways that you can just get some, what we call bite-size learning that you can learn what you have time for, learn what you need quickly, those sorts of products.

So we're doing a lot of that. And then we're providing for people who are training others, resources, which we call a toolkit, to help you train people in your workplace setting that you can then use as a template and adjust as needed to bring concepts into the places where you're at. So all of those are our training activities.

There's a ream of other things we're working with all of the states and jurisdictions, many jurisdictions, city level jurisdictions. We're working with a number of community colleges, actually through a partnership with the H, HRET, which is the health, the AHA’s foundation arm, the American Hospital Association’s foundation arm to bring education directly to community colleges and community college programs. So that's just the surface. There's a lot more than that, but as you can see it all centers around the needs of the healthcare workers on the front lines and trying to get them the information that they need to protect themselves and protect them.

Vickie: Wow. That's a lot. The boxes that I heard you say is primarily education, right? To our frontline workers, and also looking at different ways of doing the education through videos, podcasts, and I love how you all are rethinking about, what can they learn in five minutes versus a traditional 60 minutes, right?

Because not everyone has that amount of time necessarily. So, you know, some sprinkles of education and things that they can take away with them. And how exciting about a trainer's toolbox? That also helps, you know, having templates and things that they can run away with and just implement and add their own sort of spices to how they deliver that.

So sounds like some really great stuff. And I also appreciate you lifting some of the other organizations and partners that you all are working with, so you're not doing it alone. You're not doing this lift alone, there are others that are helping to do this lift. So a lot of great things. So I wanted to transition to the heart of why we would definitely want you to talk a little bit more, and that is the webinar that you had presented on the 28th. And the topic again of that webinar was addressing emerging infection control threats to Urban Indian organizations. It was a great webinar, I actually attended. I actually learned a lot too, I know it's probably recorded. So you get a chance to go to NCUIH and take a look at that.

But in that webinar we had at the beginning, I know that they had a breakout session and which was great, because it allowed folks to connect, but also allowed folks to unpack two questions. The first question was "what infection control challenges does your organization currently face?" Was one question that they explored.

And then the other question in the breakout room was "How is your organization addressing these challenges?" So they came back with, you know, a number of responses. They included limited resources and tests for COVID-19, lack of structured infection control training, which we had mentioned earlier with Kyle, issues with staff wearing masks appropriately, exposure to COVID-19 and reduced staffing.

Telehealth team meetings and demonstrations on appropriate PPE, personal protective equipment, such as mask and telehealth, to help preserve, resolve some of these problems. So those were some of the responses in those breakout groups with the two questions, so in your opinion, Dr. Carlson, how can healthcare staff [00:31:00] remind themselves to wear mask appropriately and what can be done to reinforce the basic IPC guidelines and to remind healthcare workers?

Dr. Carlson: Yeah, so, you know, I think that, the issue, of reminding yourself, how to wear the mask, how to wear any PPE, any personal protective equipment correctly is often one of habit. And sometimes that means you have to help get your coworkers or your family or friends to help you build that habit.

Whether it's you have a tendency to let your mask slip down below your nose, or you sometimes forget to put your mask back on. When you walk out of a room where you've been alone, thinking of it, like habit building is an easy way to go about that top process. My particular one was putting a post-it note on the door of my office that said, "Do you have your mask?"

Because in the early pandemic, that was my thing. I would forget that I didn't have my mask on and I'd go out to grab something and it would be like, "oh no, no, no. I'm the one creating the rules and I can't even follow them." But it took me a little while to build that habit up, you know? So I would treat it just like you might treat, trying to exercise, or trying to eat better and take it a small step at a time.

But, remember for yourself that you're really doing this for the protection, both of yourself and to others. And I know that for healthcare workers often, our patients are really our primary focus. And if we just remind ourselves, you know, am I re do I have everything I need to protect my patient?

And that this habit is so important to build for that reason that I'm doing this to protect my patient. In terms of reminding other coworkers, there's a lot of different ways to go about this, and obviously you want to approach people with a certain degree of human grace, right? You want to be able to recognize that people will forget sometimes that they're not wearing their mask, or they'll forget that they're not wearing, you know, that they need to keep it above their nose so just having a quick reminder of. “oops, you know, your mask is down” is one way to do it.

One of the clinics that I had the opportunity to interact with, they had created like a code, like a code nose or a code. I forget the word that they used. It was. There's something really cute, really funny, but it was just a way for them to say to each other, oops, I see your mask is down and without like calling out the worker in front of a patient, right?

To, to say, oh yeah, no, your healthcare workers mask is down. It's done so that it didn't come across , as something where a person would go on the defensive. And it was a really great idea to just have that as the expectation in the clinic, that if you saw it, you were going to call that code to the other person "Code Nose" and they would, they would put up their mask.

So I think those are some just starting ideas for how to deal with these situations that are work places.

Vickie: Thank you, habit. Absolutely. I love the post-it that idea. And so what I'm hearing you say loud and clear is be creative, right? Be creative in your workplace. How can we remind each other, but also in a gentle way, like "yo", you know, "pull up your mask", so be creative and make it a habit.

The underscoring importance is taking care of yourself and others. It made me think about when you're on the plane and they say, when the oxygen mask comes, you always cover yourself first. So this is take care of yourself first, right? Cause we have families too, that you go home to and simple messages and advice yet also very hard to create new habits, so thank you for that.

The heart of your presentation in the webinar on the 28th, you had discussed what variants were as it related to COVID-19. Can you remind folks what this is? And can you explain to our listeners why Omicron strand appears to be more infectious than prior COVID-19 strands?

Dr. Carlson: Absolutely. So a variant is another word for it as a strain and it is caused by changes in the genes of viruses. So what happens is viruses have genes just like human beings have genes that are the instructions for how to make more. And when those instructions are copied because they have to be copied out before new virus particles can get their gene packet to go out into the world and cause more infection.

Those instructions are copied, but they're often copied with mistakes. So the genes have little mistakes inserted into them. And you can kind of think of it like a school kid copying out a paragraph from a book they're going to make little errors here and there they'll spell the word wrong, they'll miss a letter or maybe a whole sentence will disappear.

So when that happens, there are some basic consequences of that, and the virus will take one of a couple of pathways. One option is that nothing happens. So the mistake is inserted, but it doesn't mean much to the virus. And it doesn't mean much to its ability to affect people. It goes out into the world and we might notice it cause we'll pick it up in the laboratory, but otherwise its not a big deal.

The most common thing that happens is that the virus can't survive. So somehow that mistake is so big that it can't put itself together, it can't get out of the cell to go infect other people, it can't copy itself again, even if it does get in and infect other people. So the most often what happens is a mistake is made and then it's a dead end.

The thing that we worry about with variants is that, there are occasions when those mistakes are inserted or taken into the genes. And the virus is built in a slightly different way, and it still survives and maybe even survives better or travels to people better infects easier, infects a little bit differently.

That is when a new variant is born. So it goes out into the world. It infects other people, spreads between people, we pick it up and goes on. The reason that variants are important for health and disease is those little mistakes that are made, also make it more difficult sometimes for our immune systems to recognize the virus is something we've seen before or something that we've been vaccinated against.

So that's when it becomes a health problem and that's when we talk about things like the antibody treatments not working as well, or the vaccines maybe having a little bit less effectiveness, that sort of thing. So that's how, that's how that develops. OMICRON is obviously a variant of COVID-19 that develops that way, we're a bunch of what w what I'm calling mistakes, there are essentially changes in how the virus is built. All of that has built into the Omicron variant and has changed the way that, it is spread between people. Not necessarily in the method, but just with the ease.

So getting to the second part of your question, which is this idea of why is OMICRON more contagious? Well, there's a lot of reasons that any variant could be more contagious, and especially, , as variants emerge, we don't necessarily know which one of these things is the biggest contributor. So we're still learning about what makes Omicron of more contagious, but there are a few things.

So it, can be better at sticking to a cell. So when it finds a cell that, it matches with it, it can invade better at sticking to that, and then getting into that cell. That can make a variant more contagious. It can be better at surviving, whether that means like surviving out in the environment or surviving in the body, surviving past immune defenses.

And then it can also make more of itself so that if you're infected when you're breathing out, more virus is being breathed out. If you have the variant than, if you were infected with the older variants of the virus or the original virus. And that actually reminds me to explain this idea of more contagious.

They think that concept came up in the webinar, and I realized I haven't talked about it yet. But when we say something is more contagious, what we mean by that is if you are infected with the new variant. So OMICRON, in this case, you will infect more people than if you were infected with the old variant or the original variant of SARS CoV-2.

So for example, if I had gotten infected with, OMICRON. I might spread it to five, six or seven people. Whereas with the original variant of SARS CoV-2, maybe I would have only managed to infect two or three people. And so, so it's actually kind of a mathematical idea of more contagious, but it just means that you spread it more and you can imagine if I can spread it to seven people instead of four then those seven people spread it to seven other people instead of four people spreading it to four, and this is all exponential growth, right? So suddenly things traveled much, much, much faster just by increasing that number a little bit.

Vickie: Wow. That's a scary, number one.

Dr. Carlson: It is, but there's a lot of good news too, in that there are a lot of ways to combat that. So, but yes, it is. It's overwhelming to think about.

Vickie: It is, and it's actually a nice transition. I have so many questions as you were talking, and that was really helpful. It made me understand why they, we all react to it differently. You know, some people have more extreme reactions to these variants than others.

That's one thing that made me think about, and the other thing too, was you in the webinar, you had used an analogy of a dog. I thought that was brilliant. I know that you gave credit to someone else about that, and that helped me to understand also, and maybe you can mention that.

What you were just talking about.

There are some good things too right. And what we could do differently. In the next question I wanted to ask in terms of our healthcare workers, what can they do differently around IPC infection prevention control now versus earlier and the pandemic?

Dr. Carlson: Yeah, so I'll start with the analogy to the dogs because they think that this helps explain the infection control part.

So this analogy, comes from my boss, Dr. Mike Bell, who likened, variance to dog breeds. So some are more or less hyper, some are more or less friendly, some are more or less active, but they're all dogs, right? And so variants are kind of the same way. Some might cause a slightly different infection pattern, some might be slightly more confused, maybe a lot more contagious. Some might be, you know, slightly less contagious. Cause that can happen too with. But they're all SARS CoV-2. So this is, this is still COVID-19. This is still SARS CoV-2 which to clarify as the virus that causes COVID-19. And so, because of, because you're still dealing with the same underlying species, the SARS CoV-2 virus, the infection control actions really.

Change the same things still apply and it becomes important to do them well. So for example, even though there are these small changes in the virus, the virus is still basically constructed in the same way and spread the same way. So a mask or an N95 respirator will still trap the virus in the same way.

And it actually doesn't trap virus so much as it traps the particles that virus travels in, which are your respiratory droplets. So it's not that you have to get different masks or better though clearly you want to make sure that you've got masks and respirators that fit well, that work well, that block particles, because you want to make sure that you're not breathing those respiratory droplets in. But it's not like the N 95 doesn't work anymore, you've got to go and you have to use like a P 100 respirator that's full face because it goes through the skin now or something. That hasn't happened. And won't, if that happens we have a new, a brand new virus at our hands.

The basic things like cleaning and disinfection, still work. Your alcohol based hand sanitizer still dissolves the envelope around the virus and kills it. Soap and water does the same thing using telemedicine and using barriers to kind of keep people distanced from each other so that they're not breathing in each other's respiratory viruses, that's still works.

So a lot of it is really about taking, again, those habits that we we've been developing now for two years and are exhausting. I know I admit that freely with everyone else, but taking those and really embracing them and reinforcing them so that they are, they are even more important now where that increased contagiousness.

The decreased effectiveness of vaccines just opens up that door a little wider for somebody to get infected. So that increases the importance, but the fundamentals haven't changed. And that's really important to remember about variants, is that they often don't, they stay the same.

Vickie: That was really, really informative.

And again, back to basics for folks in terms of practice, like washing your hands and the mask. So thank you for responding to that project first-line is in its second year. What did you learn in the first year and what impact do you hope to make in year two?

Dr. Carlson: Yeah. One of our teammates likens us a little bit to a startup and we, it felt that way.

We really, you know, in the middle of the pandemic, just like everyone else had to gather our wits about us and try to get things together and out to healthcare workers. We fortunately together with our partners have just gotten a lot of feedback from healthcare workers and from partners about. What works, what doesn't, what do people need and how do they need it?

And so our second year is really focused on taking those lessons from the frontline and putting them into action. And so we hope to bring more things that are. Again, bite-size that you can get in your work environment that are practical for the work you're doing. We're hoping to bring things that are not just another government video that are entertaining enough, that you're not feeling like you're doing your annual trainings every time you watch, where we want things that speak to you and your own experiences that you can say, yep.

This is my experience of the pandemic. And then recognize that. Genuinely that everyone is exhausted and that, you know, there's in many ways, a crisis for health care workers that they've been living now through for two years, but that is, is worsening in the middle of this odd McConnell wave. And that we are not here to make your life even more burdensome by trying to bring these things out. But rather we are trying to do our best to help you so that we can take some burden away, whether that's just reassuring you about what works and what doesn't, so that you know, what you can do, whether that's making sure that you have the information that you need at your fingertips, whether that's helping to get our guidance to you in a way that is clear that you can use it and make use of, of sort of the pathways that we've set out. All of that is our goal for year two in big broad strokes, but we recognize where we are in the pandemic. And we've learned a ton from the people who have gone on this journey with us over the first year.

So we hope to, to bring it back better as we move through.

Vickie: Thank you. I love who, I don't know who he had noted, but you had said someone had mentioned to you, well, you are really still in the startup phase, right? I appreciate that because, that just sort of puts a light on, we're still learning where we're evolving and we're listening and we're trying to pull and thread out, what makes sense in some things , may pan out and some things may not, some things may have to be modified in the delivery of what you all are experiencing or putting together to help the frontline warriors that you all are serving. And also just want to underscore what you had note, because I think that's a, it's a really heartfelt message.

Like being exhausted, just sort of acknowledging everyone. Like we're tired, everyone's tired, right? Uh, whether whatever your role is in, in trying to everyone do this heavy lift together and just recognizing that. So giving grace to ourselves in that way. So I appreciate you talking about how the second year is we're listening to you all, we're pulling out what we think might make sense and trying and seeing what works and that we're also still learning. We're learning with you and doing the best that you all can to support them, so I appreciate all of that.

Anything else that you want to add? I know we talked a lot about the webinar, but also your role in this project.

And just where you're at? What's bubbling up for you at this time?

Dr. Carlson: Oh, goodness, I we've covered so much, which is wonderful. You know, I think just to speak more even to NCUIH's role, we're looking forward to in year two continuing to take this guidance and really bring it into the context of Urban Indian Health and into urban Native peoples who are looking for information in their languages, in their cultural context, that's relevant to their place in time of what's going on. And so I think it's really a special opportunity for us to be able to go on this journey with NCUIH and to understand and listen to a group that maybe hasn't gotten the attention of infection control in historically speaking, in terms of trying to adjust and consider our recommendations in their cultural context.

So that is exciting for me as well. And just a pleasure and honor to be on this journey with everybody.

Vickie: Thank you for that. Beautiful. I wanted to bring Kyle back in our space. Kyle, I know you've been listening and hearing what Dr. Carlson shared with us was there anything else that you wanted to add or emphasize based on what you heard?

Kyle: No, I think Dr. Carlson did a phenomenal job, as usual subject expert.

It began to just echo again, we're looking at a special approach to deliver these updates to our Native populations. So that's, I would just emphasize on that. And again, great job Dr. Carlson on that.

Vickie: Thank you. Well, I just want to say to both of you, Dr. Carlson and Kyle, Ahéhee, (thank you) so much for showing up fully and sharing your wisdom, sharing words of inspiration, words of hope, but also some practical, basic things that we need to be mindful of to protect ourselves and others around us.

Any final thoughts before we close out?

Kyle: I would just say the precautions that are in place by the CDC now masking washing your hands, those things that if you could, at the minimum, do those, that is doing a lot. So I would just say that

Dr. Carlson: and just to, add on what Kyle said, the best I can say is exactly what he said, that you know, start with the basics, and you're very, very, very far down the path already. And it's really a pleasure to once again, to be here today and to be able to talk with everybody.

Vickie: Thank you. All right, I appreciate you both again, have a wonderful rest of the week and take care. Today, we talked about CDC, national collaborative Project FIRSTLINE infection prevention and control training initiative and the work and urban in an organizations to prepare healthcare staff on the front lines to battle emerging and reemerging disease threats.

We discussed the key messages from the NCUIH is hosted webinars. Addressing emerging infection control threats to urban Indian organizations and reminded our healthcare warriors that the CDC guidelines on infection control are still relevant and effective against COVID-19 the flu and cold viruses to obtain additional training information and resources.

Contact the NUICH Project FIRSTLINE team at IPC@NCUIH.org

This is your host Vickie Oldman. Ahé’hee (Thank you) for joining us.